Summary (in one sentence): Pudendal nerve pain (pudendal neuralgia) can be intensely real while standard medical tests — MRI, routine nerve conduction studies, and EMG — come back normal because of the nerve’s size and location, the limits of the tests (many test motor function but the problem is sensory), intermittent or positional compression, central sensitization, and issues of technique and timing; accurate diagnosis therefore relies heavily on clinical criteria, targeted procedures (diagnostic nerve blocks) and a careful multidisciplinary evaluation. PubMed+2NCBI+2

Introduction: the puzzle of severe pelvic pain with “normal” tests

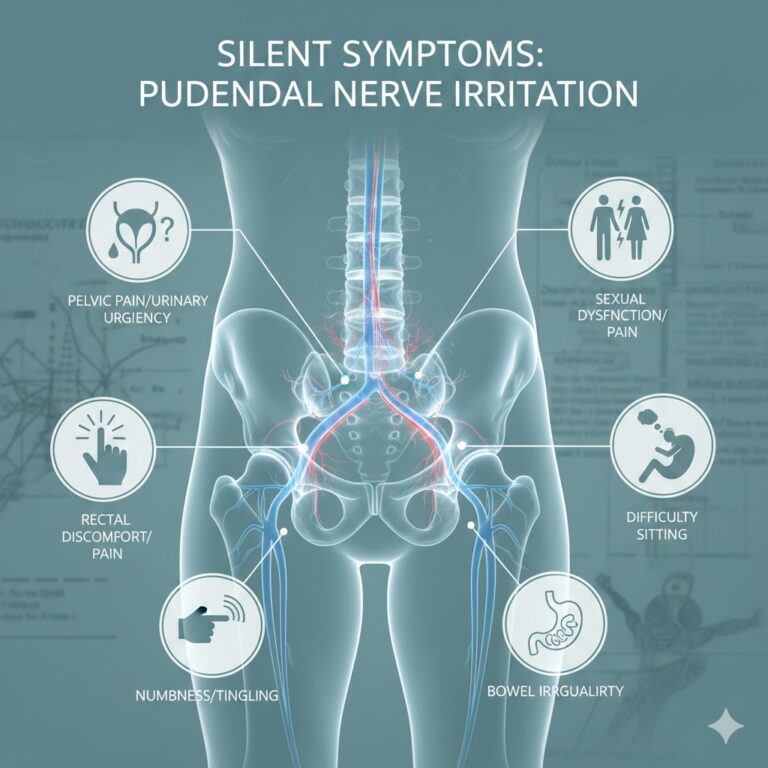

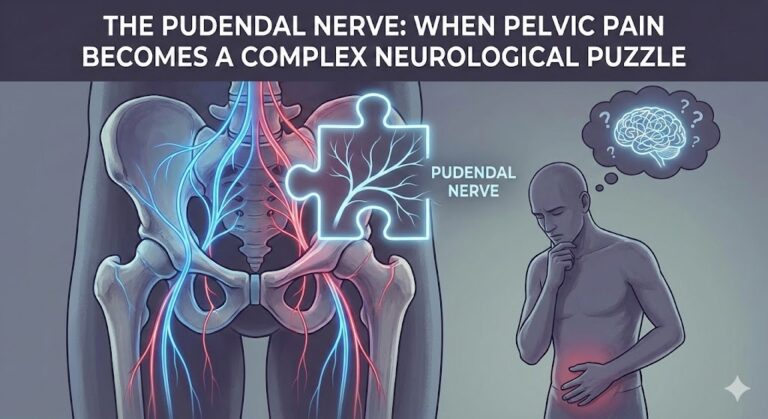

Many people with chronic perineal, genital, rectal, or pelvic pain describe crushing, burning, or electric-like pain that worsens with sitting. Yet when they undergo routine imaging (MRI, CT) or standard neurophysiology (EMG, nerve conduction studies), the results may be unremarkable. This disconnect — intense subjective pain without objective findings on common tests — is confusing and distressing for patients and clinicians alike.

Understanding why this happens requires a clear look at how the pudendal nerve is built and how our diagnostic tools work (and fail). This article explains those reasons in depth, presents the standard diagnostic approach, suggests what testing can be helpful, and offers guidance about next steps and realistic expectations. It is written for patients, caregivers, and clinicians who want an evidence-aware, practical explanation.

Quick anatomy and function: why the pudendal nerve is special

Basic anatomy

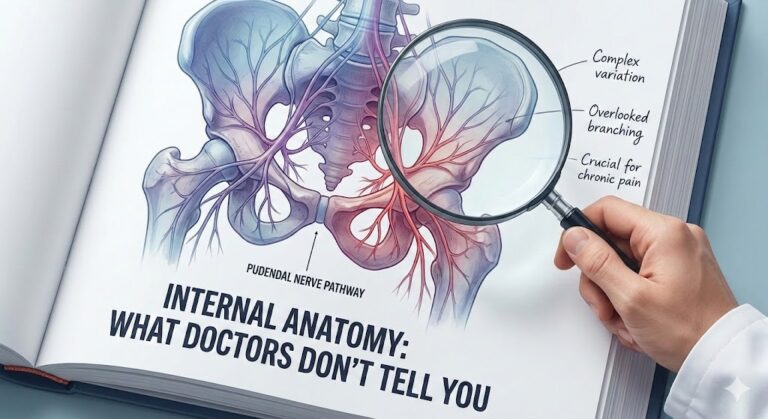

The pudendal nerve arises from the sacral plexus (nerve roots S2–S4), exits the pelvis through the greater sciatic foramen, wraps around the sacrospinous ligament near the ischial spine, then re-enters the pelvis via the lesser sciatic foramen and travels in Alcock’s canal (pudendal canal) along the lateral wall of the ischioanal fossa. It splits into sensory and motor branches that supply the perineum, external genitalia, anal sphincter and parts of the urethra and pelvic floor musculature.Mixed nerve with predominantly sensory signals

The pudendal nerve is a mixed nerve — it carries both sensory and motor fibers — but the pain problems (pudendal neuralgia) are predominantly sensory: burning, shooting, numbness, or hypersensitivity in the nerve’s dermatome (perineum, distal rectum, penis/clitoris, scrotum/vulva). Motor dysfunction (sphincter weakness) is less common and often subtle. This fact is central to why some tests miss the problem.

What common tests look for — and what they miss

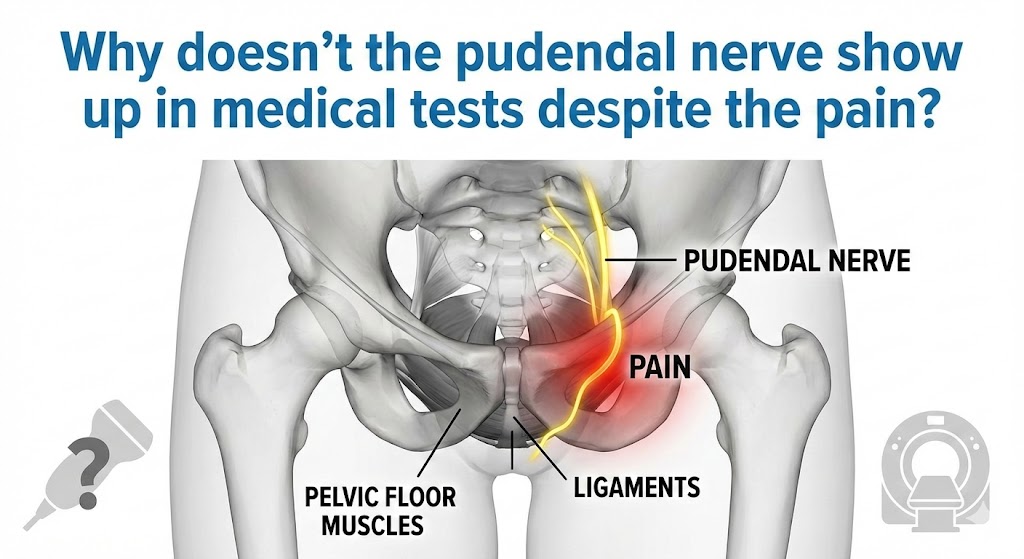

MRI and CT: excellent for structure, poor for tiny or intermittent nerve changes

- What they do well: MRI and CT identify gross structural causes — tumors, major traumas, bone fractures, large hematomas, or obvious masses compressing pelvic nerves. MRI can also show inflammatory changes in many peripheral neuropathies when specialized protocols are used.

- What they miss: Standard pelvic MRI sequences are optimized for organs and bones, not for a thin peripheral nerve tucked into Alcock’s canal. The pudendal nerve is small and may be compressed transiently (position-dependent) or show only subtle signal changes that fall below routine MRI resolution. Even when specialized MR neurography (high-resolution sequences targeting the pudendal canal) is used, findings can be nonspecific or absent in clinically confirmed cases. Thus a normal MRI does not exclude pudendal neuralgia. NCBI+1

EMG and nerve conduction studies: motor-focused and timing-dependent

- What they measure: Standard electrodiagnostic tests (electromyography — EMG, nerve conduction studies — NCS) largely assess motor fibers and muscle electrical activity. Some specialized tests (pudendal nerve terminal motor latency — PNTML, somatosensory evoked potentials — SSEPs) exist for the pudendal nerve.

- Why they can be normal: If the pathology is mainly sensory (most pudendal neuralgias are), motor testing can be normal. Also, denervation signs on EMG may take weeks to develop after an injury — so early exams can be falsely negative. Some pudendal-specific tests (PNTML) are operator-dependent, inconsistent across labs, and have limited sensitivity/specificity. In short, a “normal EMG” does not reliably exclude pudendal nerve dysfunction. ScienceDirect+1

Diagnostic nerve blocks: the single most informative test

A targeted anesthetic block of the pudendal nerve (often CT- or fluoroscopy-guided) that temporarily relieves the pain is taken as strong objective evidence the pudendal nerve is the pain source. This is included as one of the Nantes diagnostic criteria for pudendal neuralgia. Because nerve blocks directly test pain transmission, they are more useful than routine imaging or motor-focused electrodiagnostics for confirming a sensory neuropathy. PubMed+1

Detailed reasons tests can be normal despite real pain

Below are the most important, evidence-backed explanations.

Sensory-predominant injury: your tests are not designed for sensory-only dysfunction

Most routine nerve tests focus on motor output (muscle responses) or conduction velocities which are easier to measure for larger, myelinated motor fibers. Pain often comes from small-diameter sensory fibers (A-delta and C fibers) that are not assessed by standard NCS/EMG. If only these sensory fibers are damaged or sensitized, motor tests remain normal.

The nerve lesion may be intermittent or positional

The pudendal nerve is commonly irritated by sitting or certain pelvic positions or activities. Compression can be dynamic — occurring only when sitting, cycling, or during childbirth, and disappearing when standing. Imaging performed while the patient is supine and relaxed will not capture a compression that occurs only with loading.

3) The nerve is small, deep, and near complex pelvic anatomy — imaging resolution limits

Even modern MRI has a finite spatial resolution; small focal entrapments or perineural scarring in Alcock’s canal can be below that threshold. Standard pelvic MRI protocols aren’t tuned to look specifically at the pudendal canal; only MR neurography with dedicated coils and sequences improves detection, and even that can be insensitive or interpreted inconsistently. The Journal of Neuroscience+1

4) Timing matters: changes can take time to show on electrodiagnostics

If a nerve was recently injured, EMG signs of denervation (fibrillation potentials, motor unit changes) may take weeks to appear. Conversely, in very chronic cases adaptation or partial reinnervation can make findings subtle. Tests done at the wrong time relative to the injury can therefore be falsely reassuring. ScienceDirect

5) Central sensitization and pain syndromes

Long-term peripheral nerve irritation can produce central nervous system changes (central sensitization) — the spinal cord and brain amplify and maintain pain even after the peripheral drive lessens. In such cases the pudendal nerve may not show an ongoing structural lesion, while the patient still experiences real neuropathic pain driven by peripheral and central mechanisms. Standard imaging and peripheral nerve tests will not detect these central changes.

6) Overlap with other pelvic and non-neurologic causes

Pelvic pain has many contributors — pelvic floor muscle spasm, proctologic conditions (proctalgia fugax), gynecologic problems, urologic conditions, sacroiliac or lower lumbar radiculopathies, and psychosocial factors. Some of these cause similar symptoms and can co-exist. Tests negative for pudendal injury might suggest the need to search for other causes or recognize mixed pain mechanisms. The Nantes criteria explicitly include absence of objective sensory loss because sensory changes can be subtle or absent on simple examination, further complicating objective proof. PubMed+1

Technical and operator issues

- Improper electrode placement, suboptimal MRI protocol, inexperienced neurophysiology technicians, or low-volume centers unfamiliar with pudendal testing can reduce diagnostic yield.

- Specialized procedures (PNTML, MR neurography, CT-guided nerve block) require experienced teams; without them, false negatives increase. Sandwell and West Birmingham NHS Trust+1

What the evidence and diagnostic guidelines sayNantes criteria (clinical diagnosis)

Because objective tests are limited, experts proposed clinical criteria (the Nantes criteria) that remain central to diagnosing pudendal neuralgia. The “five essentials” are:

- Pain in the anatomical territory of the pudendal nerve.

- Pain worsened by sitting.

- Pain that does not awaken the patient from sleep.

- No objective sensory loss on clinical examination.

- Pain relieved by diagnostic pudendal nerve block.

These criteria emphasize the primacy of history and response to a targeted block, recognizing that imaging and electrodiagnostics are often non-diagnostic. PubMed

Role of imaging and electrodiagnostics in guidelines and reviews

Recent reviews and textbooks (StatPearls, JNS Focus, specialized neuroradiology literature) state that imaging is mainly useful to exclude alternate causes and occasionally to find entrapment signs on targeted MR neurography. Electrodiagnostic tests may help in selected cases (e.g., to demonstrate denervation or asymmetric motor impairment) but are insensitive for primarily sensory pudendal neuropathies and have variable reliability. Therefore, neither MRI nor EMG alone can reliably rule out pudendal neuralgia. NCBI+1

Practical diagnostic pathway: how clinicians should proceed

Step 1: careful history and focused pelvic/perineal examination

A detailed history is the most powerful diagnostic tool. Key features: pain distribution, relation to sitting or pelvic activities, onset after trauma/childbirth/surgery/cycling, exacerbating and relieving factors (standing vs sitting), and whether pain wakes the patient from sleep.Step 2: apply Nantes criteria and consider differential diagnoses

Use the Nantes criteria as a clinical framework. At the same time exclude proctologic disease, pelvic inflammatory disease, endometriosis, spinal radiculopathy, urologic or gynecologic causes through targeted history, exam, and selective tests (urine tests, pelvic ultrasound when indicated).

Step 3: targeted imaging if indicated

Order MRI or CT when structural disease is suspected or to exclude other causes. If a high suspicion of pudendal entrapment remains and local expertise is available, request MR neurography with pudendal canal–focused sequences. Tell the radiologist that pudendal neuropathy is suspected — that improves the chance they will use appropriate protocols. The Journal of Neuroscience+1

Step 4: targeted electrodiagnostics in selected cases

If motor symptoms (sphincter weakness) exist or if the clinician needs objective conduction data, request specialized tests (PNTML, pudendal SSEPs, anal sphincter EMG) from an experienced neurophysiology lab. Interpret results cautiously; normal tests do not exclude neuropathy. ScienceDirect+1Step 5: diagnostic pudendal nerve block (gold standard for localization)

A CT- or fluoroscopy-guided pudendal nerve block that produces significant short-term pain relief is one of the strongest objective supports that the pudendal nerve is the pain generator. Because of its diagnostic and potential therapeutic role (sometimes repeated blocks reduce pain), this procedure is central in the evaluation. AJR Online+1Step 6: multidisciplinary assessment and treatment planning

Because of complex and overlapping mechanisms (peripheral entrapment, pelvic floor myofascial pain, central sensitization), a multidisciplinary team — pain medicine, pelvic floor physiotherapy, colorectal/urogynecology, neurology/neurosurgery, psychology — is often needed to design a personalized plan.

Why the delay in diagnosis happens (patient and system factors)

- Rarity and low awareness: Pudendal neuralgia is uncommon and under-recognized by many clinicians, leading to misdiagnosis.

- Symptom overlap: Similar symptoms appear in more common conditions (hemorrhoids, prostatitis, pelvic floor dysfunction), so initial workups often chase those diagnoses.

- Limited access to specialized testing/centers: MR neurography, experienced neurophysiology labs, and CT-guided blocks are available only in some centers.

- Fragmented care: Patients may see multiple specialists (urology, gynecology, gastroenterology) without a coordinated plan.

- Test limitations: As discussed, conventional tests can be normal, which can falsely reassure providers and patients. NCBI+1

When to suspect pudendal neuralgia: red flags and typical clues

- Pain localized to the perineum, distal rectum, penis/clitoris, scrotum/vulva.

- Pain markedly worse with sitting and improves with standing.

- Pain that does not frequently wake the patient at night (a useful clue in Nantes criteria).

- Onset after pelvic trauma, childbirth, pelvic surgery, prolonged cycling or direct perineal compression.

- Partial relief after a pudendal nerve block. PubMed

How clinicians and patients can improve the chance of diagnosis

For clinicians

- Take a targeted history using Nantes-like questions.

- Communicate with radiology about suspected pudendal neuropathy so they can optimize MRI protocol.

- Refer to centers experienced in pudendal testing (MR neurography, CT-guided blocks, specialized neurophysiology).

- Use diagnostic pudendal block early when suspicion is moderate to high.

For patients

- Document symptom patterns (what triggers pain, sitting vs standing, sleep interference, onset details). A pain diary with activities helps clinicians.

- Seek a clinician familiar with chronic pelvic pain or pudendal neuralgia (pain specialists, pelvic floor clinics).

- Ask about diagnostic block if imaging and EMG are normal but symptoms fit the clinical pattern.

- Keep realistic expectations: diagnosis may take time and often requires a multi-pronged approach. NCBI+1

Treatment implications of a “normal” test result

A normal MRI or EMG does not mean “no problem.” Management is guided by symptoms and clinical assessment rather than solely by imaging findings. Therapeutic options include: conservative measures (activity modification, sitting cushions), pelvic floor physiotherapy, neuropathic pain medications, nerve blocks, botulinum toxin in select cases, and—when clear entrapment exists and other measures fail—surgical decompression in specialized centers. The choice depends on whether the dominant issue appears to be ongoing mechanical entrapment, pelvic floor myofascial pain, or a neuropathic pain syndrome with central sensitization. NCBI+1

Common myths and misunderstandings

Myth: “If the MRI and EMG are normal, the pain is imaginary.”

Fact: Pain is a subjective but biologically real experience. Normal standard tests are common in sensory-predominant neuropathies. Diagnosis must combine history, targeted diagnostic blocks, and multidisciplinary assessment. PubMed

Myth: “Only surgery can fix pudendal neuralgia.”

Fact: Many patients improve with conservative and interventional pain management (physiotherapy, medications, injections). Surgery is reserved for carefully selected patients and outcomes depend on accurate selection and surgical expertise. PubMed

Key takeaways (practical checklist)

- A normal MRI or EMG does not rule out pudendal neuralgia. NCBI

- The Nantes clinical criteria and response to a diagnostic pudendal nerve block are central to diagnosis. PubMed+1

- Standard tests miss small-fiber sensory dysfunction, positional entrapment, and central sensitization. ScienceDirect+1

- Seek evaluation at a multidisciplinary pelvic pain center when possible. NCBI

Further reading and reliable references

- Labat J-J, Riant T, Robert R, et al. Diagnostic criteria for pudendal neuralgia by pudendal nerve entrapment (Nantes criteria). Pain. 2008. PubMed

- StatPearls — Pudendal Neuralgia. (NCBI Bookshelf / StatPearls). Comprehensive clinical review (2024). NCBI

- Filler AG. Diagnosis and treatment of pudendal nerve entrapment syndromes. J Neurosurg. 2009; focused on advanced imaging and surgical approaches. PubMed

(These three sources are good starting points; specialists may recommend more recent MR neurography or procedural-focused papers.)

Practical example (short case to illustrate)

A 38-year-old cyclist develops burning perineal pain after a long ride. Routine pelvic MRI and EMG are normal. Pain worsens with sitting and improves when standing. A CT-guided pudendal nerve block produces dramatic temporary relief. The patient is diagnosed with pudendal neuralgia and begins a program of activity modification (no cycling), pelvic floor physiotherapy, and a series of therapeutic nerve blocks; surgery is considered only if conservative measures fail. This scenario shows how targeted blocks and history — not routine imaging — often make the diagnosis.

When to get second opinions and specialized care

If you have persistent perineal/genital/rectal pain with a normal standard workup, consider referral to:

- A pelvic pain clinic or pain medicine specialist experienced in pudendal neuralgia.

- A center offering MR neurography and CT-guided pudendal blocks.

- A multidisciplinary team (pain medicine, pelvic physiotherapy, colorectal/urogynecology). Early referral can reduce diagnostic delay and improve outcomes. AJR Online+1

Final words for patients

Your pain is real even if routine tests are normal. Diagnosis of pudendal neuralgia relies heavily on history, pattern of symptoms, and targeted procedures — not just conventional scans and EMG. Advocate for a focused evaluation (Nantes-guided history, targeted MR neurography where available, and diagnostic pudendal nerve block) and multidisciplinary care. With the right team and realistic expectations, many people achieve meaningful symptom improvement.

Medical / Professional Disclaimer: This article provides general information about pudendal neuralgia and diagnostic testing and is not a substitute for professional medical judgment. If you are experiencing pelvic or perineal pain, seek evaluation by a qualified healthcare professional. Management must be individualized and may require input from specialists. The content above cites peer-reviewed and reputable clinical sources but does not replace an in-person clinical assessment. PubMed+1